Christian Déséglise, HSBC’s Group Head of Sustainable Infrastructure and Innovation, leads the bank’s global efforts in Just Energy Transition Partnerships – or JETPs – with Indonesia and Vietnam. He explains why they are powerful tools for decarbonisation.

They offer a faster way out of coal

JETPs are becoming more popular because they bring key stakeholders together to enable a clean, fair energy transition in emerging economies that rely heavily on coal.

Essentially, they’re multilateral financial agreements aimed at accelerating the phase-out of fossil fuels, in a way that addresses the social consequences of doing so.

The model first gained attention in 2021, when a USD8.5 billion deal was announced for South Africa, in partnership with France, Germany, the United Kingdom, United States and European Union. This was followed by a USD20 billion package for Indonesia and a USD15.5 billion agreements for Vietnam last year. Deals for India and Senegal are expected to follow.

Partnership is the operative word

Many parties have a role to play in the decarbonisation of a country. These include domestic stakeholders, such as its citizens, government and utility providers, as well as external partners that help finance the transition. These are a mix of climate finance donors as well as public and private sector investors – typically G7 governments, development banks and financial institutions.

A JETP allows the key players to work together on designing, funding and implementing a plan that’s tailored to the country’s specific needs and characteristics. It’s underpinned by a commitment from the country to step up its climate ambitions, against the promise of funding and support from its external partners.

The ‘just’ part is vital too.

Retiring coal-fired power plants and replacing this energy with renewables will be a key focus of the plans. But this must be done in a way that minimises any negative impact. That’s why the third goal of JETPs is to implement policies that support affected communities – for example, ensuring workers in coal regions can access retraining.

They could unlock new technologies

The initiatives will also encourage investment into green technologies and industries that boost the country’s economic development. With the right input, Indonesia – the world’s largest producer of nickel – could become a major manufacturer of batteries for electric vehicles, for instance.

Where do banks like HSBC come in?

The private sector was not represented at the launch of South Africa’s JETP. This was a shortcoming, in my view. By bringing the private sector on board from the outset you can create conditions that help mobilise finance at scale and unlock far greater sums.

In the case of Indonesia and Vietnam, the financial sector is now represented by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). Within this, HSBC is playing a lead role, helping identify barriers to private investment in each country, as well as proposing solutions.

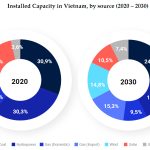

In particular, Vietnam’s JETP will mobilize $7.75bn from the International Partners Group (IPG) co-led by the EU and the UK over 3-5 years, with the facilitation of at least the same amount in private finance from GFANZ Working Group members including HSBC. We are currently working with GFANZ and Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) on next steps in terms of implementation, with HSBC’s support re-iterated by Asia-Pacific Co-CEO Surendra Rosha during a number of recent meetings including one with Deputy Prime Minister Tran Hong Ha.

As a bank we are also supporting the coal Energy Transition Mechanism, which aims to facilitate the early retirement of coal assets in Asia. This initiative, led by the Asian Development Bank, will work in service of the JETPs.

Blended finance is key

Renewable energy projects in Indonesia and Vietnam have historically struggled to access financing. The reasons for this are complex and varied – from foreign exchange and credit risk considerations to political and regulatory issues. Within working groups, we will unpick these “bankability” issues and seek ways to overcome them.

Blended-finance vehicles such as Pentagreen – HSBC’s joint venture with investment firm Temasek – could be one possible solution. It can finance projects that banks would ordinarily turn down.

These partnerships are the perfect fit for world’s local banks.

We want to play our part in supporting the transition to a more sustainable world. That’s a key part of HSBC’s strategy as a business. And we’re a global bank, but with strong local knowledge in Indonesia and Vietnam. We can bring our local knowledge and local footprint to the global community driving the partnerships.

The hard work is just beginning.

It’s early days for these agreements. They are long-term initiatives, with the initial funding packages to be disbursed over three to five years.

It’s important that all the parties remain committed and engaged over time. But if successful, I believe they can provide the template for decarbonisation across the world.

Diep Nguyen