The history of carbon credits, however, spans back to the negotiations around the Kyoto Protocol in 1996 – the first United Nations agreement for developed countries to cut emissions. At that time, carbon credits were crucial in politics, especially to gain the support of the United States, which ironically signed but never ratified the protocol.

The carbon market is now experiencing significant momentum, with new compliance markets emerging and existing ones expanding. A report by Trove Research revealed that over the past decade, $36 billion has been invested in carbon credit projects, with half of that invested in just the last three years. Since 2020, approximately 1,500 new projects have been registered, with another 1,500 in the early development stages. This surge reflects a growing global commitment to addressing climate change through carbon credit mechanisms.

These investments have protected and restored around 30 million hectares-an area equivalent to Italy. This highlights the tangible impact of carbon credit initiatives in safeguarding vital ecosystems and mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into the global atmosphere. However, increased scrutiny of carbon credits for offsetting has raised concerns about whether they result in real, verifiable emissions reductions.

A carbon credit is a tradable certificate or permit that represents the right to emit one metric tonne of CO2 or an equivalent amount of another GHG. These are credits generated by projects/activities that reduce, remove, or avoid GHG emissions. Examples include reforestation and renewable energy projects, and methane capture from landfills. Companies or individuals can purchase these offsets to compensate for their emissions.

However, not all activities that result in GHG emission reductions can claim for carbon credits. Instead, they have to follow the strict methodologies of international organisations that register and issue carbon credits to generate real and valid credits for trading. Vietnam is under the development of the country’s own rules, but it must not deviate much from the international standards to make sure credits originating in Vietnam are as high quality as international ones.

For a carbon credit to be valid, four minimum criteria are required: the project needs to be “additional” – i.e., it would not have taken place if there was no revenue from the sale (or expected sale) of carbon credits; the quantification of the difference of emissions between the actual and baseline (reference point or scenario that would have occurred if the project had not been implemented) needs to be accurate; the carbon credit’s emissions reduction or removal must not be unexpectedly reversed; and the carbon emission reductions need to be independently verified.

The four criteria mean the project must go beyond business as usual-a fact often omitted in newspaper coverage. Firstly, the investment is needed to implement the project itself to generate carbon credits. Existing projects that do not factor in revenue from selling credits when making the initial decision do not qualify. Proving this additionality requires specific methods and approaches and must be verified by the independent parties.

Carbon credit verification and registration is a rigorous process that involves various steps to ensure the legitimacy of the credits and also incurred transaction costs. The transaction costs must be covered until the credits can be sold, which usually takes at least two years for registration and issuance.

Therefore, revenue from selling credits is often just the icing on the cake, providing an additional income source after transaction costs are deducted, to enhance the commercial attractiveness of the venture.

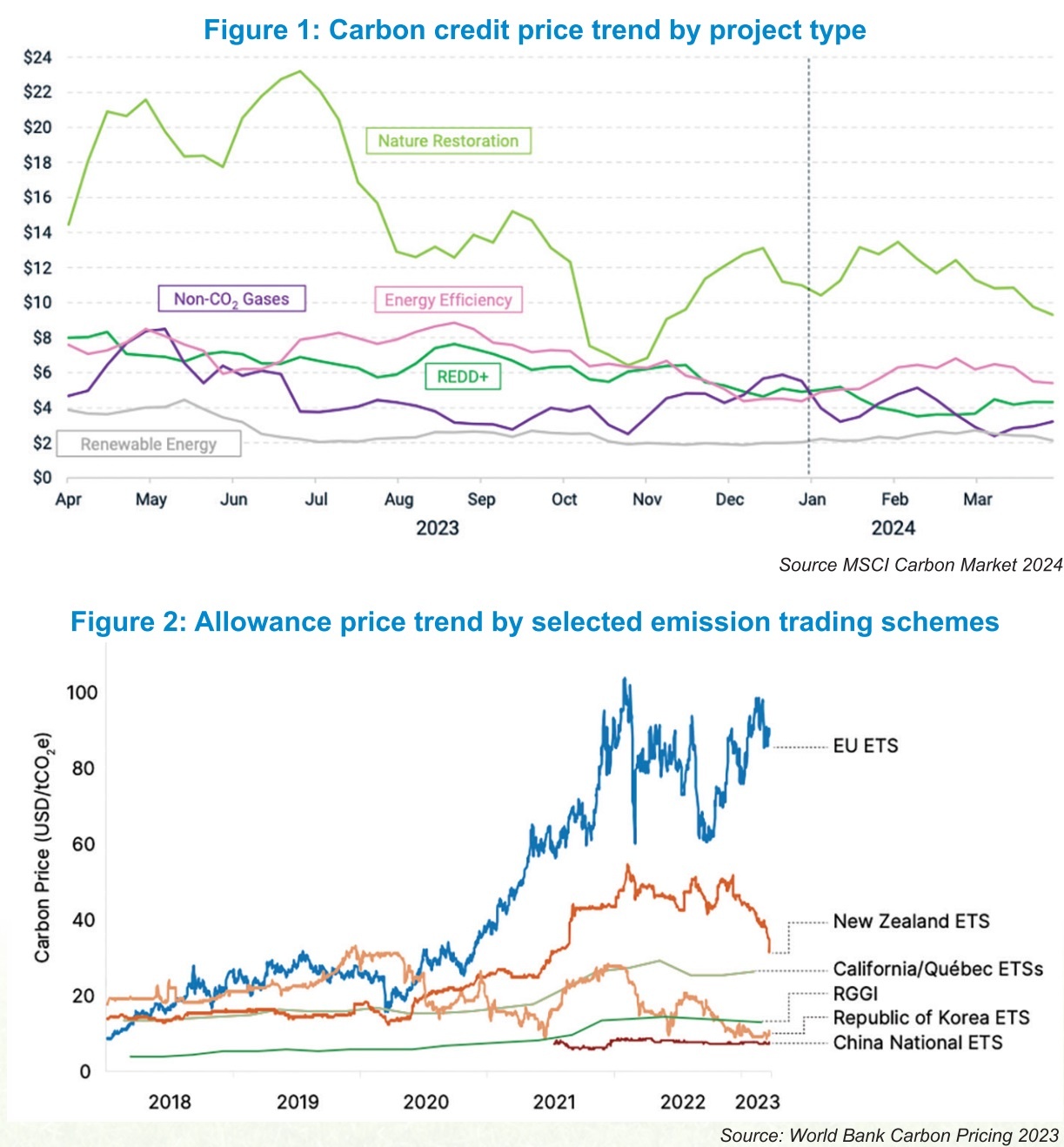

Buying carbon credits hinges on their scarcity and the local benefits they provide, such as improving living conditions or reducing pollution (see Figure 1). With numerous project types generating credits at varying prices, costs fluctuate based on project type, location, and co-benefits. Comparing the carbon price for a renewable project in Vietnam with a nature-based one in Laos is not meaningful, for instance.

Some have even compared the price of credits generated from Vietnam under the voluntary market with carbon prices under the regulated carbon market (allowances under the European Emission Trading Scheme and the carbon tax in Singapore), or even the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism tariff. However, this is like comparing apples to oranges, and their principles differ significantly.

The growth of the carbon market in Vietnam is a continuation of the trading of credits under the Clean Development Mechanism since the first batch of carbon credits were issued for Vietnam in 2008 for the Rang Dong oil field associated gas recovery and utilisation project. To date, about 48.6 million carbon credits have been issued for projects from Vietnam under different mechanisms.

The carbon credit market is expected to become more competitive and more stringent. Hence, only those who have a solid understanding of relevant trends then will be able to form an impression of whether or not a given project qualifies for carbon credits, and what the expected costs and benefits might be.

Dang Hong Hanh