The market buzz around renewables is growing in Southeast Asia.

In Thailand, the authorities are mulling another round of clean energy tenders just months after an earlier tranche was oversubscribed by three times. Developers are flocking to the Philippines after it allowed full foreign ownership of projects end-2022.

Meanwhile, solar panel builders are considering Indonesian bases after Singapore businesses signed a US$38 billion deal to develop big projects there. Several of the manufacturers will be expanding from existing factories in Vietnam.

All this is happening while Vietnam, the de-facto renewables frontrunner in Southeast Asia that houses almost 70 per cent of the region’s installed solar and wind power capacity, has been stuck in governance limbo for some two years and counting. Its policy plan for the power sector this decade has still not been finalised, while fresh rounds of auctions and pricing plans that would spur new solar and wind projects are nowhere on the horizon.

The ongoing freeze has rattled investor confidence in the country and could be a major stumbling block in future developments, especially as other Southeast Asia nations step up their green energy transitions, analysts and industry players say.

Internal turmoil

The latest roadblock in Vietnam is understood to be caused by an anti-corruption drive within the government, which has already culminated in the sudden resignation of its former president in January, and is blocking policy progress across the country’s economy.

Industry insiders tell Eco-Business that the investigations involve pricing deals the government had issued in previous years for renewable energy projects, further blocking progress on this front.

There had been few updates on auctions or pricing of renewable electricity since 2018, when the government extended hefty above-market fixed payment rates to producers. The deadline to receive those subsidies passed in 2021 and developers have not heard back on what new rates they would be getting since.

This lack of clarity means that renewable energy targets appear to be “hung in the air”, said Liming Qiao, head of the Asia branch of industry group Global Wind Energy Council, referring to a draft 10-year power development plan that projected 7 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind by 2030.

The “Power Development Plan 8” (PDP8), as the policy document is named, has also been delayed by two years. Several drafts have been passed between government echelons since 2021, and there have been changes to how much of a role clean power would play. In February 2021, total renewables capacity in 2030 was supposed to add up to 41 gigawatts (GW); by September that year, it had dropped to under 33GW.

It could be especially difficult for prospective entrants to the market, according to Eric Miller, chief executive of Singapore-based renewables developer Pacific Impact Development. There are also other unanswered questions in PDP8, such as the denomination for long-term contracts with state-owned Vietnam Electricity, the sole power offtaker in the country, and how long such deals can be – developers generally favour longer timeframes of over 20 years.

“There are a significant number of issues which will impact how sponsors see the risk, and how lenders see whether projects are bankable or less bankable, depending on the choices that are made,” Miller said.

As it stands, Pacific Impact Development is working on a renewables project in Vietnam, and the firm is taking a “wait-and-see” approach, Miller shared.

Vietnam’s renewables policy void comes at a time when other countries in the region are making progress on their own green energy transition. Qiao said the Philippines is now regarded a strong competitor for wind power, after its government launched competitive auctions and removed a requirement for renewable energy projects to have 60 per cent local ownership last year.

Foreign developers are already starting to turn away from Vietnam, Qiao said, with some shrinking their offices there. Among them is Singapore-based firm The Blue Circle, which had let go half of its staff in 2021.

“We could not continue to pay our development staff, when there was nothing to develop. We had absolutely no visibility,” said The Blue Circle founder and chief Olivier Duguet. The rest of the staff are mainly running the three operating wind power projects the firm had already connected to the grid in past years.

Other than the Philippines, Duguet also sees opportunities in Thailand, where the government is looking to launch a call for clean energy projects worth over 3.6GW. A 5.2GW call for applications for wind, solar and biogas projects late last year, pegged to a fixed buying price for the electricity, saw developers put in almost 17GW of proposals, according to local news outlet Bangkok Post.

Hui Min Foong, a research analyst at analytics firm S&P Global Commodity Insights, said the key renewables markets to watch in Southeast Asia are now Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand. Apart from success with renewable energy tenders, these countries also have better power grid infrastructure to deal with the intermittent output of solar and wind farms, Foong explained at a commodities market forum last week.

Vietnam’s industry and trade ministry has not responded to requests for comment.

Victim of its own success?

Counting green electrons, Vietnam leads the solar and wind energy buildout in Southeast Asia by a big margin.

The country’s renewable power push started in earnest in 2019, buoyed by the high prices the government was guaranteeing developers for their clean electricity. Some contracts provided about US$100 per megawatt-hour of green power generated, against the country’s retail electricity price of US$80.

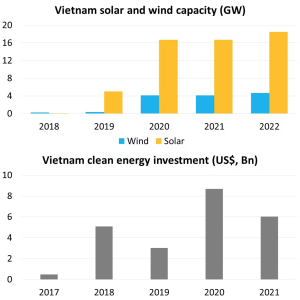

As a result, installed solar capacity rose nearly 45-fold from just 105 megawatts (MW) to nearly 5GW in capacity in 2019, before more than tripling to 16.7GW in 2020. The wind power boom followed that year, with capacity rising 11 times to over 4GW. The latest figures stand at 18.5GW of solar and 4.6GW of wind, according to data by the International Renewable Energy Agency.

In contrast, neighbouring Cambodia, Laos and Thailand have less than a quarter of Vietnam’s wind and solar capacity combined. Indonesia, with triple the population of Vietnam, has 50 times less green power.

Southeast Asian countries have generally struggled to court renewable energy investors. Construction projects in the region carry higher risk profiles and higher interest rates compared to developed markets. In many countries, fossil fuels reign supreme, leaving few gaps for renewables to plug.

Vietnam’s early success with renewables appear to have surmounted these challenges, but how it did so also created new ones with lasting effects to this day.

For one, its electricity grid struggled to handle the varying power loads that solar panels and wind turbines put out based on time of day and weather, instead of when people actually need electricity. Regulators mandated supply cuts on renewable power plants, resulting in financial losses.

Foong said the Vietnamese government estimates that US$3.6 billion annually will be needed in the coming years to upgrade the power grid. The authorities opened up grid investments to the private sector last year, which could help money flow in – as could a US$15.5 billion “Just Energy Transition partnership” deal it signed with wealthy countries and financiers in December 2022.

Nonetheless, the troubles with the grid meant that authorities “completely lost trust” with its fixed-price guarantee system – termed a feed-in tariff – as a way to support renewables development, according to Qiao.

Several project developers had asked the government to extend the scheme’s 2021 deadline due to Covid-19 delays, but it took until early this year for the government to approve the move. Even so, the offtake price was lowered for these projects, understood to total several gigawatts of capacity.

Some solar projects would now be getting only up to about US$51 per megawatt-hour of power generated, a level that could be financially unviable, said Foong.

Several markets in Southeast Asia have moved to an auction system instead, where developers bid to deliver electricity at the lowest price – a system that could help more efficient projects stand out, and reduce government spending. Vietnam has indicated it wants to launch auctions, but details are sparse.

Nonetheless, developers Eco-Business spoke to are not pulling out of Vietnam entirely.

The coal-to-renewables transition in the region will still happen eventually, “irrespective of the regulations and policies on the ground”, Pacific Impact Development’s Miller said. The firm is focusing on the Indonesia and Vietnam markets, which both still rely heavily on cheap but pollutive coal for power generation.

“Coal is being phased out partly because it is unpopular, but also the whole ecosystem that would normally support coal projects is no longer there – there’s no longer financing and insurance for coal-fired projects,” Miller added.

“We’re hopeful [about Vietnam], and although we recognise there is more uncertainty today while PDP8 gets sorted out, we’re here to stay. It is a big market and we believe that renewables are going to play a significant role in the generation mix going forward,” he said.

“Vietnam paints a fantastic [macroeconomic] picture. It is one of the tiger economies of Southeast Asia with 100 million inhabitants…it is basically the factory for China,” said The Blue Circle’s Duguet.

But in a country where close to half the utility-scale solar and wind projects are developed by foreign investors – according to a tabulation by Thailand-based news outlet Mekong Eye – their opinions hold weight.

“I’m trying to pass this message all the time to the Vietnamese authorities, to be very careful, because it will need international investors, not only for renewables. It is greatly damaging right now to the image of Vietnam as an investable country,” Duguet said, referring to the troubles in the renewables sector.

Renewable energy investors sent a letter to Vietnam’s Prime Minister and other officials earlier this month, Bloomberg reported, urging favourable policies and an end to the impasse.

Liang Lei